"Our people lived in settlements on both sides of the Nansemond River where we fished (with the name “Nansemond” meaning “fishing point“), harvested oysters, hunted, and farmed in fertile soil.

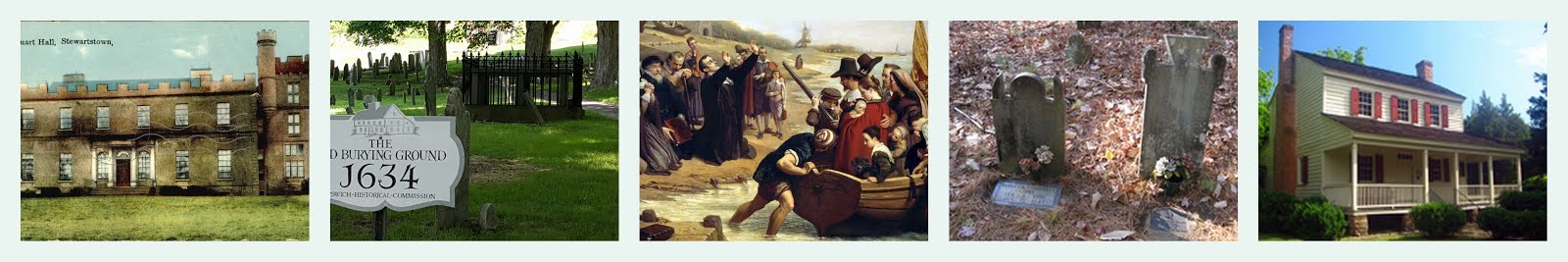

"When the English arrived in Powhatan territory in the early 1600s, several decades of violent conflict ensued with the Anglo-Powhatan Wars lasting from 1610 to 1646.** In this period of time the English displaced the Nansemond from our ancestral land around the Nansemond River into surrounding areas. Members of the Nansemond tribal community reacted differently to the upheaval which caused a schism in the tribe. Some families assimilated to an English lifestyle while others adhered to a traditional lifestyle.

"In 1638 John Bass, an English minister, married Elizabeth, the daughter of a Nansemond chief, in a union that would mark the beginning of a small segment of our tribe’s migration from the Nansemond River toward the northern border of the Great Dismal Swamp. Concurrently, other segments of our tribe were aligning with neighboring tribes to resist assimilation. Nansemond people were documented living among the Meherrin and the Nottoway in the 1600s and 1700s.

"The political differences among Nansemond people did not mean they no longer lived as family or kin. People of Indian ancestry suffered social and legal scrutiny throughout Virginia and over time many Nansemond families moved away from Norfolk County, VA, into counties further west and across the state line into North Carolina."

(Above is quoted from Nansemond History site.

------------------------

The below information is historically given, about the Anglo Powatan wars.

**Encyclopedia Virginia says the first Anglo-Powatan war was from 1609-14, mainly against Jamestown fort. (quoted below, as well as Second and Third Anglo-Powatan wars. I included a lot of information that I hadn't found elsewhere...but it may be more than you're interested in reading.)

"The First Anglo-Powhatan War was fought from 1609 until 1614 and pitted the English settlers at Jamestown against an alliance of Algonquian-speaking Virginia Indians led by Powhatan (Wahunsonacock). After the English arrived in Virginia in 1607, they struggled to survive through terrible drought and cold winters. Unable to adequately provide for themselves, they pressured the Indians of Tsenacomoco for relief, which led to a series of conflicts along the James River that intensified in the autumn of 1609. Powhatan ordered something like a siege of the English fort, which lasted through the winter of 1609–1610 and precipitated the so-called Starving Time. This was the Indians’ best chance to win the war, but the English survived and, after the arrival of reinforcements, viciously attacked. Using terror tactics borrowed from Queen Elizabeth‘s conquest of Ireland, English soldiers burned villages and towns and executed women and children. Eventually they defeated the Nansemonds and Kecoughtans at the mouth of the James and the Appamattucks near the falls. After two years, Captain Samuel Argall captured Powhatan’s daughter Pocahontas in the spring of 1613 and turned his prisoner into the leverage necessary to make peace. Although not all scholars see the First Anglo-Powhatan War as a distinct conflict, at least from the Indians’ perspective, many argue it to be England’s first Indian war in America."

Further consideration is given to how the Native Americans actually looked at their own wars between each other's tribes.

"Because of this constant, small-scale warfare [among the tribes], some scholars have argued that, at least from the Indians’ perspective, assigning the term “Anglo-Powhatan War” to this period of conflict doesn’t make sense. “This dichotomy [of war and peace] is nearly irrelevant in Native American cultures,” the anthropologist Frederic W. Gleach has written, “where war and peace were often ongoing, simultaneous processes …” For the English, however, wars generally came equipped with clear-cut beginnings and endings; wars were persistent and thorough.

"... Over the winter, [1609-1610] the 240 men, women, and children at James Fort endured the Starving Time, during which they fed on snakes, rats, mice, musk turtles, cats, dogs, horses, and possibly even each other. By May 1610, only about sixty of the colonists remained alive. Remarkably, the Sea Venture‘s passengers and crew arrived at Jamestown on May 24, having survived in Bermuda for ten months. One of the new colonists, William Strachey, later wrote that the particulars of the “Famine and Pestilence” he found within the fort were more “then I have heart to expresse.”

Sir Thomas Gates opted to abandon Virginia, but as the colonists sailed down the James, they encountered a ship bearing the new governor, Thomas West, baron De La Warr, and a year’s worth of supplies. Fausz describes De La Warr’s arrival, along with the “new vengeful resolve that took root” among the colonists, as “the critical turning point in the First Anglo-Powhatan War.”

"Then, on July 9, 1610, the English launched a vicious counterattack against the Powhatans.

"... the [English] “use of deception, ambush, and surprise, the random slaughter of both sexes and all ages, the calculated murder of innocent captives, the destruction of entire villages” all were new to America. While the Indians could be just as violent as the English [with cruel tortures] certain restraints were built into their method of waging war. The practice of avenging particular slights tended to personalize, and so limit, the scope of conflict. The Indians’ desire to take prisoners also acted as a restraint. Prisoners served as symbols of success and targets for rage; they also could serve as adoptees into the chiefdom or as hostages to be traded. Because it threatened the lives of these potential prisoners, unlimited violence was not always useful. In addition, Indians traditionally spared the lives of chiefs, women, and children.

"...1611 ... Then on March 28, an ill De La Warr sailed for the West Indies, leaving George Percy in charge pending the arrival of the new deputy governor, Sir Thomas Dale.

"In June, Dale led a hundred armored soldiers against the Nansemonds at the mouth of the James River, burning their towns. Then in September, after receiving a shipload of reinforcements, the colonists attacked upriver, gaining enough ground to found the new settlement of Henricus. In December, Dale’s men used Henricus as a launching point for new attacks, defeating the Appamattucks once and for all. Dale now had the mamanatowick stuck in a vice between the English gains on both ends of the river and the Monacans and other non-Algonquian-speakers beyond the falls.

For the next two years, the elderly Powhatan could do little but lie low, his authority weakened. Indications of this are the number of English plantations established along the James despite periodic Indian resistance. Captain Samuel Argall, meanwhile, explored the northern, more vulnerable reaches of Tsenacomoco and there found the Patawomecks to be especially willing trading partners. This was partly due to the influence of Henry Spelman, the young boy who had fled Powhatan in 1609 after the ambush of John Ratcliffe’s party. Having matured into a reliable interpreter, Spelman now served as a liaison between Argall and Iopassus (Japazaws), weroance of the Patawomeck town of Passapatanzy. The relationship bore unexpected fruit when, in April 1613, Argall learned that Pocahontas was staying in Passapatanzy. Using the stick of English military might and the carrot of a potentially lucrative partnership, Argall convinced Iopassus to help him kidnap Pocahontas, ironically giving to the English what the Indians traditionally prized in war: a valuable prisoner. (As for Spelman, he seemed to personify the blurred lines between friend and foe, native and English, war and peace. A few years later, he would just escape execution on the charge of bad-mouthing the English to Opechancanough.)

After concluding treaties with the Accomacs and Occohannocks on the Eastern Shore, Argall and his superior, Dale, attempted to use Pocahontas to win concessions from her father. But for a year Powhatan only stalled, until, in March 1614, Dale, Argall, and 150 English soldiers—with Pocahontas in tow—paddled deep into Pamunkey territory, home to Opechancanough and Tsenacomoco’s most fearsome bowmen. At present-day West Point, where the York and Mattaponi rivers meet, the Englishmen disembarked and faced down several hundred Indians. When, after two days, neither side was willing to fire first, the colonists returned to Jamestown. The war ended on a note of anticlimax.

The First Anglo-Powhatan War had begun with a truce and a cultural exchange when young Henry Spelman had gone to live with the weroance Parahunt. Now it ended with another truce and cultural exchange. This time, Pocahontas, Parahunt’s half-sister, decided to remain among the English. During the stalemate of 1612–1613, she had converted to Christianity, and in April 1614 the English informed her father that she intended to marry John Rolfe, one of the Sea Venture‘s passengers. Powhatan assented. The English and the Indians did not share many understandings about war, but they both agreed that this marriage could bring peace.

And for a while it did. Although Pocahontas died in England in 1617, and her father a year later, the peace held and the English took advantage by expanding their settlements far beyond Jamestown. After Rolfe introduced a saleable grade of tobacco to the colony, plantations were established up and down the James, while the Indians bided their time.

On March 22, 1622, Opechancanough’s warriors struck the colony suddenly and without the usual restraint, launching the Second Anglo-Powhatan War (1622–1632).

The Second Anglo-Powhatan War was fought from 1622 until 1632, pitting English colonists in Virginia against the Algonquian-speaking Indians of Tsenacomoco, led by Opitchapam and his brother (or close kinsman) Opechancanough

The headright system begun in 1618 granted land to new immigrants who, in turn, sought to make their fortunes off tobacco. As English settlements pressed up the James River and toward the fall line, Indian leaders devised a plan to push them back and, in so doing, assert their supremacy over the newcomers. On March 22, 1622, Opechancanough led a series of coordinated surprise attacks that concentrated on settlements upriver from Jamestown and succeeded in killing nearly a third of the English population.

What followed, then, was a ten-year war in which the English repeatedly attacked the Indian food supply. After the conflict’s only full-scale battle, fought in 1624, colonists estimated that they had destroyed enough food to feed 4,000 men for a year. Peace finally arrived in 1632, but by then the balance of power in Virginia had tipped toward the English. The colonial population had grown significantly and Opechancanough’s power waned.

Opitchapam and Opechancanough evidently did not wish to eliminate the English settlements; otherwise, they would not have contented themselves with striking a single major attack. What, then, did they hope to accomplish through the March 22 assault?

The Powhatan Indians’ behavior provides several important clues to their intentions. First, twenty of the twenty-four attacks fell on the upriver settlements, where the spread of the English settlements had most directly intruded on the original, core nations of the paramount chiefdom. (Powhatan had inherited several chiefdoms in this area in the 1570s, then greatly expanded his influence and control over the next few decades). The older English settlements, especially Jamestown and other downriver places where the colonists had originally been allowed to live, were less hard-hit. Second, many of the English dead were mutilated, adding to the humiliation of their resounding defeat. According to Edward Waterhouse, George Thorpe’s killers, “with such spight and scorne abused his dead corps as is unfitting to be heard with civill eares.” Third, Opitchapam and Opechancanough followed through after their victory with studied silence rather than with additional raids, evidently assuming that a single devastating blow would communicate their message.

Given the evidence above, the Powhatan Indians seemed satisfied that the March 22 attacks had fulfilled their purpose: to put the English in their proper place, both literally and figuratively. They expected the English to remain in a subordinate position to Powhatan’s (now Opitchapam’s) paramount chiefdom and to remain geographically confined to the downriver settlements near Jamestown or the remote Eastern Shore. Thus the anthropologist Frederic Gleach has aptly characterized the March 22 attacks not as a “massacre” (which suggests a simple, savage randomness) or as an “uprising” (which assumes that the Powhatan Indians had already been subdued by the English), but rather as a “coup … a sudden and vigorous attack” intended as a corrective blow to the misbehaving English living in the midst of Powhatan’s people.

Despite appearances, however, the English colonists’ retreat did not mean that they understood the Powhatan Indians’ message. On the contrary, they assumed that their intent, according to Edward Waterhouse, was to “destroy us.” Their withdrawal from outlying settlements was purely strategic. In fact, some regarded the March 22 attacks as the perfect excuse to wage unrestricted war against the Powhatan Indians. “Our hands which before were tied with gentlenesse and faire usage, are now set at liberty,” Waterhouse wrote. He continued, “[We] may now by right of Warre, and law of Nations, invade their Country,” and then “enjoy their cultivated places” while reducing the Indians “to servitude and drudgery.”

But how? There were still far more Indians than English colonists. The first step was to find allies and food to sustain the colony through the next year. Rather than counterattack right away, the English initially focused their attention on the Potomac River and the Eastern Shore, trading and strengthening alliances with more distant chiefdoms while they developed a strategy for repaying the Powhatan Indians.

The strategy that emerged was devastatingly effective. “To lull them the better in securitie,” John Smith wrote, the English deliberately “sought no revenge till thier corne was ripe.” Then, throughout the fall and early winter of 1622–1623, they sacked the most vulnerable Powhatan villages (timing their raids to “surprize their corne”). When Wyatt listed his military assets he counted not only fighting men, but also, according to the governor’s Council, those who were “serviceable for caryinge of corne.” Even diplomacy revolved around food: the English agreed to a truce in the spring of 1623 in order to let both sides plant their crops, but they fully intended to resume their “feede fights” after the corn ripened.

The climax of the war came in the summer of 1624. In the only full-scale battle of the decade-long conflict, sixty Englishmen landed near a key Powhatan town, one inhabited by members of the Pamunkey Tribe. For two days the two sides fought to a stalemate. While the struggle continued on the open battlefield, a few Englishmen took advantage of the diversion to burn the Indians’ fields, destroying enough food, the governor’s Council claimed, “to have sustained four thousand men for a twelve-month.” When the Powhatan Indians finally realized the extent of the damage, they “gave over fightinge and dismayedly, stood most ruthfully lookinge one while theire corne was cutt downe.”

Virginia’s leaders deliberately prolonged the war for another eight years after the climactic victory of 1624. Although the Powhatan Indians mounted occasional raids and light skirmishes, the English generally took the offensive.... The fighting continued well into 1632, when a new governor finally signed an agreement—unpopular with Virginia’s elites, who were profiting from the “feede fights”—to end the war.

The Powhatan Indians were not exactly vanquished. Their 1632 agreement with the English merely ended the war; there is no indication that it contained any humiliating provisions or admissions of defeat. (The original was destroyed during the American Civil War; notes taken by the early Virginia historian Conway Robinson described it only as “a peace.”) The Powhatan Indians still outnumbered the English, and they retained control of considerable territory (greater in extent than that of the English) north of the James River.

At the end of the 1630s the English population (now grown to nearly 8,000) exceeded that of the Powhatan Indians, and early in the 1640s colonists began taking up lands on the north bank of the York River, along the Rappahannock, and even as far north as the Potomac River.

The war also significantly altered colonial society. The March 1622 attacks set in motion an investigation that led to the dissolution of the Virginia Company of London. In 1624 James I assumed direct Crown control of the colony.

"... by early in the 1640s the colonists were once again encroaching on Powhatan communities. By then the Powhatan Indians, still numerous, independent, and led by Opechancanough, were prepared to fight another war against the English: the Third Anglo-Powhatan War (1644–1646).

April 18, 1644

Opechancanough and a force of Powhatan Indians launch a second great assault against the English colonists, initiating the Third Anglo-Powhatan War. As many as 400 colonists are killed, but rather than press the attack, the Indians retire.

Sharing with Amy Johnson Crow's Generations Cafe on FB, where 52 Ancestors 52 Weeks offers these prompts. Next week is "Fast"