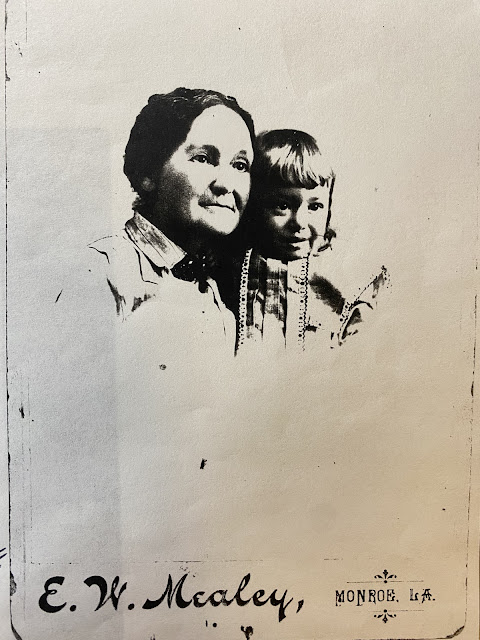

First, I want to honor another ancestor in my own family. Today I give the portrait of Ada Phillips Swasey Rogers (1886-1964). Here she is candidly walking with her youngest son, James, in 1936...showing her strong determination which she lived daily. She was extremely dedicated to Christian Science and her family of four young men with an extremely smart husband.

Now let's drive along the Blue Ridge Parkway...before the leaves start to turn colors and learn about some old tales.

This is the valley today. Pretty agrarian. I guess losing the last buffalo isn't on anyone's mind, until they stop at this "overlook" and think about it.

But there are more stories than just a sign. From Google I discovered this interesting article, which is a bit convoluted. I believe it's likely several pieces were cobbled together. Remember a couger in North Carolina was the same as a panther, or mountain lion, and often called a Painter (thus the name of my own cat.)

Bull Creek Stories

by Rob Neufeld

Joseph Rice, bison killer; and children of conscience

When Joseph Marion Rice claimed his two hundred acres of Bull Creek bottomland in 1792, he had few European American neighbors. The Rhiems (Reems) had settled north beyond Craven’s Gap. The Davidsons were in the Swannanoa Gap. The Gudgers were down the wagon road near the Swannanoa River.

Several years earlier, after The Treaty of Paris, Rice had sat down with the Cherokee around what has become the Dry Pond at the end of Parker Road. According to a family history by Holt Felmet, Rice “was granted, by the Indians, a sun of land…what he could walk around and stake between sun-up and sundown.”

|

| Samuel and Margaret Brank Hughey after the Civil War, Photo courtesy Frances |

Rice began building a community. In 1799, work started on a road connecting Beaverdam and Bull Creek. One day, a shaggy bull bison made its way up its old path toward Craven Gap and ultimately into history.

“The last buffalo seen in this locality was killed nearby in 1799 by Joseph Rice, an early settler,” a sign reads at the Bull Creek Valley overlook on the Blue Ridge Parkway.

In a version of the story fictionalized by great-great-grandson Rex Redmon in “Bits of Beaverdam,” the bison “had searched the valley of the Shawano an entire day seeking others of his kind.” His lonely bellowing attracted the attention of Joseph Rice, who shot it for its meat and hide.

Rices have long responded to historical forces with a sense of remorse. Joseph’s grandson, John Longmire Rice, opposed the Civil War, but, according to history passed down to Felmet, John “agreed to serve in the army, but would not bear arms.” In charge of the horses in Will Thomas’ Legion, he got sick, and was sent home. He arrived just before Christmas, 1864, suffering from black tongue, malnutrition so serious that he could not be fed.

John’s brother, James Overly Rice, whose cabin in Beaverdam is a historical landmark, had helped round up Cherokee women and children for the Trail of Tears in 1838. Redmon recalls that his grandmother and great aunt “remembered hearing that the forceful removal of the Indians, against their will, from their ancestral homes was more than my grandfather could bear. They said he cried when he told the story.”

“According to oral tradition,” Redmon relates, “James Overly entered the military in lieu of a Creasman man to whom he was indebted.” He died Mar. 8, 1863 from measles contracted in camp. He is buried in an unmarked grave with 138 other Confederate soldiers in Ringgold, Georgia.

James’ cousin, Margaret Brank, (pictured above) whose mother, Elizabeth Rice, had married into a Reems Creek family, had inherited a slave, George the Tanner, from her grandmother, Margaret Young. After the Civil War, Margaret’s husband, Samuel Hughey, told George, “You’re free to go, you can go live with your people,” according to Ray Rice, Elizabeth’s thrice-great nephew.

George went, and came back a few weeks later. He told Hughey, “I want to live the rest of my days right here with you.” He is buried in Rice-Hughey Cemetery.

A healing happened in Bull Creek,

but Rices still hear cries from the past

When the last bison of the Blue Ridge revealed itself to Joseph Rice on Bull Creek in 1799, it seemed like an American prophecy. In his ancestors’ homeland, hunting had been a restricted privilege, but in the New World, game offered itself up to men.

In a Cherokee story of origin, Kanati, the “happy hunter,” rolls back a rock to emit just one wild creature, which he shoots. Rice shot his solo offering too, but it was a different era. The American belief in individual rights and unlimited bounty had begun to produce some ill omens.

Rice’s paternal grandmother, Ann Cooper, had been born in the Virginia Colony, one of the world’s first corporate ventures. His paternal grandfather, Richard Rice, had come from Dingle, Ireland, where his family had been dispossessed of its estate.

Retaining a landed self-assurance through moves to Virginia and North Carolina wildernesses, the Rices wedded themselves to a mountain identity. In 1840, Joseph Rice joined fifteen Revolutionary War veterans in supporting the Whig candidate for president, William Henry Harrison, against their likely allegiance to the Democrat, Martin Van Buren. Mountain loyalties ruled.

Advertising in Horace Greeley’s publication, “The Log Cabin,” they rallied for Harrison, after a Baltimore journalist had sneered at Harrison’s alleged preference for a barrel of hard cider, a log cabin, and a pension instead of the White House.

Elected, Harrison soon died from pneumonia, caused by his tendentious inauguration speech in 16 degree weather. John Tyler took over, fulfilling the reason he’d been selected as Vice President, to attract States Rights supporters. The coming storm, caused by westward expansion and the formation of pro- and anti-slavery states, would put a generation of peaceful Rices in Confederate graves.

James Overly Rice, Joseph’s grandson, enlisted at age 43, and died of measles in camp. His son, William Philetus, died in battle at Chickamauga. Another son, John Marion, got sick, received a furlough, and died at home.

The 1840s produced another legacy. James’ cousin, Rebecca, daughter of Elizabeth Rice and Robert H. Brank of Reems Creek, conceived a child out of wedlock. “Miss Rebecca has a baby,” Robert Brank Vance (future Brigadier General) wrote his younger brother, Zebulon (future Governor), in 1843. “It would have been better for her if she had been in her grave but I must stop.”

Rebecca’s baby, Eliza, grew up to marry a man twice her age, Leander Stewart, a “Northern minister,” whose Swannanoa church split over the slavery issue. Refused a separate house away from a crowd of Stewarts, Eliza took her son, Chester, back to Reems Creek.

Reems and Bull Creeks cradled a healing. A Reems Creek Church commemorative program honored both General Robert Vance and 89-year-old Rebecca Brank in 1894. In Bull Creek, Raphael and Frank Rice, James Overly’s great-nephews, bedded down in the loft of their father’s sturdy house, listening to the cries of a figure from the past: Uncle Joe Ray, a seven-foot tall Civil War veteran, suffering from gangrene in his house through the woods.

The pathway and the panther

There’s a path that leads through deep woods over Craven Gap, connecting Bull Creek with Ox Creek. Today, the Blue Ridge Parkway bisects this passageway, the mounded median of which betrays its use as a stagecoach road two hundred years ago.

Joseph Marion Rice, first settler, had run a stock stand alongside it, providing a rest stop for drovers headed to South Carolina markets. During the Civil War, two of Joseph’s great-granddaughters, Sarah Rosey and Mary Matilda Rice, set out one morning from Beaverdam and headed into the Elk Mountains to deliver canned goods to their aunts in Bull Creek.

“You may stay and visit for the day, but you must be home before dark,” their mother, Mary Wolfe Rice told them, according to an account passed along by Rex Redmon in “Bits of Beaverdam.” Mary also instructed her daughters not to accept any food in return, regardless of their aunt’s wishes.

As in fairy tales, the girls did not heed the warnings. They left late and took cured meat. Two miles from home, they heard “the nerve-shattering cry of the big black cat,” and managed to save themselves by stalling the panther with meat tossings.

There is much history in this story. The girls’ father, James Overly Rice, had migrated to Beaverdam to build a now historic home. James’ sisters-in-law, Martha Stephenson, wife of John Longmire Rice, and Rosannah Ray, a widow, resided in Bull Creek. Nestling in coves, pioneer communities maintained communication via woodland paths.

|

A party sets off from Riceville for an excursion in the nearby mountains, c. 1920. The man is Arthur Lee Hughey, great-grandson of Joseph Marion Rice. To his right is his neighbor Mary Crichton

|

James and John were away with the Confederate Army, and took their horses, which is why, in the story, the girls ride a mule. Yet, there is much myth in the story as well, and it is significant.

It is the cougar, not the black panther, that had made the southern mountains its stalking ground; and, according to scientific accounts, it had been extirpated by 1800. Furthermore, Redmon notes that his father’s mother had told him that it had been her father that had encountered the panther. But family tradition favors the girls, which is a better choice. It brings in the effects of the Civil War, and creates a sense of vulnerability.

Another part of the family mythology—flight from Europe, where hunting grounds had been gated by aristocrats—calls for a panther tale. William Gilmore Simms in his novel, “The Cub of the Panther,” portrays a Boone-like Western North Carolina hunter who is upbraided by a lady for trespassing on her estate. He responds that he’s saving her from varmints, for “an old painter…wouldn’t stop to ax ef the woman was a fine rich woman.”

The romance of wilderness is real. Ray Rice, great-grandson of Rosannah Ray, used to go up into Riceville forest to fox hunt. It was not unlike the hunters Fred Chappell portrays in his novel, “Brighten the Corner Where You Are,” in which storytelling was the hunters’ object—until the hero’s father prods his fellows to confirm the treeing of a devil-possum, which turns out to be a bobcat.

Ray, as a teen, had listened to his uncle, Carrol Hall, and his fellows, tell tales by a campfire while their dogs announced their exploits in woods now threatened by development and timbering. The stories are forgotten, but they seem so consequential today.

(Source,

Google)

Blue Ridge Parkway

Sharing with Sepia Saturday this week.

I had already compiled this post before Hurricane Helene arrived, which meant I couldn't update my post to Sepia Saturday until now, Mon. 9.30.24 evening. I've evacuated to a cousin who lives in South Carolina and will share more on my "When I Was 69" blog soon.