My friends seemed to enjoy knowing the were traveling the route that these rebel soldiers had traveled...the same twists and switchbacks.

From last week...

October 7th

ON THIS DAY in North Carolina history…

1780:

“If you do not desist your opposition to the British Arms, I shall march this army over the mountains, hang your leaders, and lay waste your country with fire and sword.”

“If you do not desist your opposition to the British Arms, I shall march this army over the mountains, hang your leaders, and lay waste your country with fire and sword.”

So says British Major Patrick Ferguson to the persistent annoying threat of the Overmountain Men. By the end of this day, he will have reason to regret those words. By the end of this day, British Commander Lord Cornwallis will have his confidence shaken so badly he will never recover. By the end of this day, the course of the American Revolution will have changed forever, and a small elevation just a few miles outside of Charlotte called Kings Mountain will go down in history as the beginning of the end for the British Army in America.

British Major Ferguson can probably be forgiven for thinking he is operating from a position of strength. So far in the South, the British Army has moved pretty much as it wished. Cornwallis has achieved a brilliant victory at Camden, SC, and after a couple of weeks rest has moved on to invade North Carolina and capture Charlotte. It is here the British began to realize that North Carolina is a different world from South Carolina. The opposition is so persistent and constant, the NC Militia using Indian tactics to harass every British movement, that Cornwallis likened it to a hornet’s nest.

In response, British Major Patrick Ferguson issues the declaration above. Ferguson’s force protects Cornwallis’ left flank during the advance into North Carolina. Ferguson is a soldier’s soldier, determined and disciplined. He is a brilliant military strategist, an experienced field commander, and is generally regarded as the best marksman in the British Army. But he has seriously miscalculated by thinking his threats will cow the western North Carolinians. Instead, they take him at his word, and come boiling out of the mountains to solve the problem he presents. The Overmountain men, ex-Regulators who had fled to the mountains after the Battle of Alamance 10 years earlier, now come rolling back. After assembling at Gillespie Gap (today it is the location of the Museum of North Carolina Minerals on the Blue Ridge Parkway), they come down the escarpment to meet up with the NC Militia at Morganton. Together the patriot force then begins to move south, heading for Rutherfordton. Nearly all the North Carolinians are on horseback, all are volunteers, not one of them is paid, nor is there a Continental Army officer among them. They move without military training, but with Indian stealth and cunning.

Ferguson meanwhile has gotten word of a Patriot ‘Army’ moving in his direction. He isn't particularly worried, but he does move his forces back east closer to Charlotte and Cornwallis. He camps on a 60-foot elevation the locals called a mountain: Little Kings Mountain.

ON THIS DAY, the Patriots catch up to Major Ferguson. Led by Isaac Shelby and John Sevier, they are able to approach and almost surround the ‘mountain’ without being detected. At the last minute British sentries detect the Patriots, and with Ferguson issuing commands, quickly form ranks. As the Patriots begin to fight their way up the sides of Little Kings Mountain, Ferguson orders his men to fix bayonets and charge down. Under the organized ranks and fearsome British bayonets, the Patriot forces are driven back. And here’s where it should have ended.

However, the Overmountain men didn’t know they were supposed to be defeated. To Ferguson’s surprise, the Patriots simply regroup, and swarm back up the mountain, shooting as they come. Again the British drive them back. And for a third time the Patriots rally, and come back up the hill. The British line is beginning to show holes, and everywhere it is thin. This time, at about the same time as Ferguson is shot out of the saddle, dead, the British line disintegrates, and the Patriots swarm over the crest of the hill. The battle is over. The rest of Ferguson's force is captured, their supplies burned, and Major Ferguson himself buried on top of Kings Mountain.

Over the next several days, the Patriot militiamen disband, returning to their homes. The Overmountain Men re-cross the Appalachian Mountains; Colonel Benjamin Cleveland and Major Joseph Winston take charge of the prisoners, which they turn over to the Moravian settlement at Bethabara, where the captives are imprisoned in a stockade.

General Lord Charles Cornwallis is shocked and disheartened by the word of Ferguson's death and the total British defeat. With the loss of one-third of his army and one of his most talented officers, Cornwallis delays his planned advance northward from Charlotte into North Carolina. Abandoning their supply wagons mired in axle-deep mud and harassed by pursuing Patriot militia, the British army retreats to Winnsboro, South Carolina for a winter camp.

The Patriot victory at Kings Mountain has other effects. The British could no longer depend on British American Loyalists in the Carolina Piedmont to flock eagerly to the British Flag. On the other hand, the Patriot spirit in the Carolinas is invigorated, and the British Southern Campaign has been dealt a substantial blow. Although more North Carolina battlefields will be required to secure America’s independence, the Battle of Kings Mountain is a turning point in the American Revolution. Yorktown is less than a year away.

Kevin E. Spencer, Author, North Carolina Expatriates

---------------------

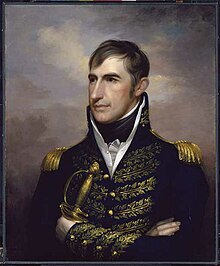

Pictured:

-An Aerial view of Kings Mountain

-Kings Mountain Sign

-Isaac Shelby, hero of Kings Mountain

-John Sevier, hero of Kings Mountain

I've posted the entire articles from Wikipedia so I have the facts (as published there). If I want the sources of all the footnotes, I'll go over to Wikipedia...

-An Aerial view of Kings Mountain

-Kings Mountain Sign

-Isaac Shelby, hero of Kings Mountain

-John Sevier, hero of Kings Mountain

Shelby and Clarke elected not to pursue the British fleeing the Battle of Musgrove Mill.[15] Instead, they set their sights on a British fort at Ninety Six, South Carolina, where they were sure they would find Ferguson.[15] However, while en route, Shelby and his men were met with news of General Horatio Gates' defeat at the Battle of Camden.[15] With the backing of General Cornwallis, Ferguson could ride to meet Shelby with his entire force, so Shelby retreated over the Appalachian Mountains into North Carolina.[16]

Following the colonists' retreat, an emboldened Ferguson dispatched a paroled prisoner across the mountains to warn the colonists to cease their opposition or Ferguson would lay waste to the countryside.[17] Angered by this act, Shelby and John Sevier began to plan another raid on the British.[17] Shelby and Sevier raised 240 men each, and were joined by William Campbell with 400 from Washington County, Virginia and Charles McDowell with 160 men from Burke and Rutherfordcounties in North Carolina.[18] The forces mustered at Sycamore Shoals on September 25, 1780.[18]The troops crossed the difficult terrain of the Blue Ridge Mountains and arrived at McDowell's estate near Morganton, North Carolina, on September 30, 1780.[19] Here, they were joined by Colonel Benjamin Cleveland and Major Joseph Winston with 350 men from Surry and Wilkes counties.[19]

The combined force pursued Ferguson to King's Mountain, where he had fortified himself, declaring "God Almighty and all the rebels out of hell" could not move him from it.[20] The Battle of Kings Mountain commenced October 7, 1780. Shelby had ordered his men to advance from tree to tree, firing from behind each one; he called this technique "Indian play" because he had seen the Indians use it in battles with them. Ferguson ordered bayonet charges that forced Shelby's men to fall back on three separate occasions, but the colonists dislodged Ferguson's men from their position. Seeing the battle was lost, Ferguson and his key officers attempted a retreat. The colonists were instructed to kill Ferguson. Simultaneous shots by Sevier's men broke both Ferguson's arms, fatally pierced his skull, and knocked him from his mount. Seeing their commander dead, the remaining British soldiers waved white flags of surrender.[21]

King's Mountain was the high point of Shelby's military service, and from that point forward his men dubbed him "Old King's Mountain".[17] The North Carolina legislature passed a vote of thanks to Shelby and Sevier for their service and ordered each be presented a pair of pistols and a ceremonial sword.[22] (Shelby did not receive these items until he requested them from the legislature in 1813.)[23]

As the colonists and their prisoners began the march from King's Mountain, they learned that nine colonial prisoners had been hanged by the British at Fort Ninety-Six. This was not the first such incident in the region, and the enraged colonists vowed they would now put a stop to the hangings in the Carolinas. Summoning a jury from their number – which was legal because two North Carolina magistrates were present – the colonists selected random prisoners and charged them with crimes ranging from theft to arson to murder. By evening, the jury had convicted thirty-six prisoners and sentenced them to hang. After the first nine hangings, however, Shelby ordered them stopped. He never gave a reason for this action, but his order was obeyed nonetheless, and the remaining "convicts" rejoined their fellow prisoners.[24]

The King's Mountain victors and their prisoners returned to McDowell's estate, early on, the morning of, October 10, 1780. From there, the various commanders and their men went their separate ways. Shelby and his men joined General Daniel Morgan at New Providence, South Carolina. While there, Shelby advised Morgan to take Fort Ninety-Six and Augusta, because he believed the British forces there were supplying the Cherokee with weapons for their raids against colonial settlers. Morgan agreed to the plan, as did General Horatio Gates, the supreme commander of colonial forces in the region. Assured that his plan would be carried out, Shelby returned home and promised to return the following spring with 300 men. On his way to Fort Ninety-Six, Morgan was attacked by Banastre Tarleton and gained a decisive victory over him at the Battle of Cowpens. Shelby later lamented the fact, that General Nathanael Greene, who relieved Gates only days after Shelby departed for home, claimed the lion's share of the credit for Cowpens, when it was Shelby's plan that had put Morgan in the position to begin with.[25]

Upon his return home, Shelby and his father were named commissioners to negotiate a treaty between colonial settlers and the Chickamauga.[26] This service delayed his return to Greene, but in October 1781 he and Sevier led 600 riflemen to join Greene in South Carolina.[27] Greene had thought to use Shelby's and Sevier's men to prevent Cornwallis from returning to Charleston. However, Cornwallis was defeated at the Siege of Yorktown, shortly after Shelby and Sevier arrived, and Greene sent them on to join General Francis Marion on the Pee Dee River.[27] On Marion's orders, Shelby and Colonel Hezekiah Maham captured a British fort at Fair Lawn near Moncks Corner on November 27, 1781.[27]

While still in the field, Shelby was elected to the North Carolina General Assembly.[27] He requested and was granted a leave of absence from the Army to attend the legislative session of December 1781.[27] He was re-elected in 1782 and attended the April session of the legislature that year.[27] In early 1783, he was chosen as a commissioner to survey preemption claims of soldiers along the Cumberland River.[28]

Shelby returned to Kentucky in April 1783, settling at Boonesborough.[27] He married Susannah Hart on April 19, 1783; the couple had eleven children.[2] Their eldest daughter, Sarah, married Dr. Ephraim McDowell, and the youngest daughter, Letitia, married future Kentucky secretary of state Charles Stewart Todd.[2][29] On November 1, 1783, the family moved to Lincoln County, near Knob Lick, and occupied land awarded to Shelby for his military service.[17] Shelby was named one of the first trustees of Transylvania Seminary (later Transylvania University) in 1783, and on December 1, 1787, founded the Kentucky Society for the Promotion of Useful Knowledge.[27]

Shelby began working to secure Kentucky's separation from Virginia as early as 1784.[30] That year, he attended a convention to consider leading an expedition against the Indians and separating Kentucky from Virginia.[2] He was a delegate to subsequent conventions in 1787, 1788, and 1789 that worked toward a constitution for Kentucky.[2] During these conventions he helped thwart James Wilkinson's scheme to align Kentucky with the Spanish.[22] In 1791 Shelby, Charles Scott and Benjamin Logan were among those chosen by the Virginia legislature to serve on the Board of War for the district of Kentucky.[9] Shelby was also made High Sheriff on Lincoln County.[9] In 1792, he was a delegate to the final convention that framed the first Kentucky Constitution.[4]

Under the new constitution, the voters chose electors who then elected the governor and members of the Kentucky Senate.[17] Though there is no indication that Shelby actively sought the office of governor, he was elected unanimously to that post by the electors on May 17, 1791.[17]He took office on June 4, 1792, the day the state was admitted to the Union.[30] Though not actively partisan, he identified with the Democratic-Republicans.[31] Much of his term was devoted to establishing basic laws, military divisions and a tax structure.[30]

One of Shelby's chief concerns was securing federal aid to defend the frontier.[1] Although Kentuckians were engaged in an undeclared warwith American Indians north of the Ohio River, Shelby had been ordered by Secretary of War Henry Knox not to conduct offensive military actions against the Indians.[32] Furthermore, he was limited by federal regulations that restricted the service of state militiamen to thirty days, which was too short to be effective.[32] With the meager resources of his fledgling state he was only able to defend the most vulnerable areas from Indian attack.[31] Meanwhile, Kentuckians suspected that the Indians were being stirred up and supplied by the British.[33]

Shelby appealed to President Washington for help; Washington responded by appointing General "Mad" Anthony Wayne to the area with orders to push the Indians out of the Northwest Territory. Wayne arrived at Fort Washington (present-day Cincinnati, Ohio) in May 1793, but was prevented from taking any immediate action because federal commissioners were still attempting to negotiate a treaty with the Indians. He called for 1,000 volunteer troops from Kentucky, but few heeded the call and Shelby resorted to conscription. By the time the soldiers arrived, winter had set in. He ordered the men to go home and return in the spring.[34]

After a winter filled with Indian attacks, including one which claimed the life of Shelby's younger brother Evan Shelby III, Kentucky militia units won some minor victories over the Indians in early 1794.[35] In spring the response to Wayne's call for troops was more enthusiastic; 1,600 volunteers mustered at Fort Greenville and were hastily trained.[36] By August, 1794, Wayne was on the offensive against the Indians and dealt them a decisive blow at the August 20, 1794 Battle of Fallen Timbers.[36] This victory, and the ensuing Treaty of Greenville, secured the territory, and although Shelby did not agree with some of the restrictions placed upon western settlers by this treaty, he abided by its terms and enforced those that were under his jurisdiction.[37]

Another major concern of the Shelby administration was free navigation on the Mississippi River, which was vital to the state's economic interests. For political reasons the Spanish had closed the port at New Orleans to the Americans. This would have been the natural market for the tobacco, flour and hemp grown by Kentucky farmers; overland routes were too expensive to be profitable. This made it difficult for land speculators to entice immigration to the area to turn a profit on their investments. Many Kentuckians felt the federal government was not acting decisively or quickly enough to remedy this situation.[38]

While Kentuckians despised the British and Spanish, they had a strong affinity for the French. They admired the republican government that had arisen from the French Revolution, and they had not forgotten France's aid during the Revolutionary War. When French Ambassador Edmond-Charles Genêt, popularly known as Citizen Genêt, arrived in the United States in April 1793, George Rogers Clark was already considering an expedition to capture Spanish lands in the west. Genêt's agent, André Michaux, was dispatched to Kentucky to assess the support of Kentuckians toward Clark's expedition. When he gained an audience with Governor Shelby, he did so with letters of introduction from Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and Kentucky Senator John Brown.[39]

Jefferson had written a separate letter to Shelby warning him against aiding the French schemes and informing him that negotiations were under way with the Spanish regarding trade on the Mississippi. When the letter was sent on August 29, 1793, it was Jefferson's intent that it reach Shelby before Michaux did, but Shelby did not receive it until October 1793. On September 13, 1793, Michaux met with Shelby, but there is no evidence that Shelby agreed to help him. In his response to Jefferson's delayed letter, Shelby assured Jefferson that Kentuckians "possess too just a sense of the obligation they owe the General Government, to embark in any enterprise that would be so injurious to the United States".[40]

In November 1793, Shelby received a letter from another of Genêt's agents, Charles Delpeau. He confided to Shelby that he had been sent to secure supplies for an expedition against Spanish holdings, and inquired whether Shelby had been instructed to arrest individuals associated with such a scheme. Three days later Shelby responded by letter, relating Jefferson's warning against aiding the French. Despite having no evidence that Shelby was party to Genêt's scheme, both Jefferson and Knox felt compelled to warn him a second time. Jefferson provided names and descriptions of the French agents believed to be in Kentucky and encouraged their arrest. Knox went a step further by suggesting Kentucky would be reimbursed for any costs incurred resisting the French by force, should such action become necessary. General Anthony Wayne informed him that his cavalry was at the state's disposal. Arthur St. Clair, governor of the American Northwest Territory, also admonished Shelby against cooperation with Genêt.[41]

In his response to Jefferson, Shelby questioned whether he had the legal authority to intervene with force against his constituency and expressed his personal aversion to doing so.

Shelby tempered this lukewarm commitment by assuring Jefferson that "I shall, at all times, hold it my duty to perform whatever may be constitutionally required of me, as Governor of Kentucky, by the President of the United States."[42]

In March 1794, perhaps in response to Shelby's concerns, Congress passed a measure granting the government additional powers in the event of an invasion or insurrection. Jefferson's successor Edmund Randolph, who actually received Shelby's letter, wrote Shelby to inform him of the new powers at his disposal, and informing him that the new regime in France had recalled Genêt. Two months later Genêt's agents ceased their operations in Kentucky and the potential crisis was averted.[43] In 1795, President Washington negotiated an agreement with the Spanish that secured the right of Americans to trade on the river.[44]

Having successfully dealt with the major challenges and issues involved in forming a new state government, Shelby left the state safe and financially sound.[44] Kentucky's constitution prevented a governor from serving consecutive terms, so Shelby retired to Traveler's Rest, his Lincoln County estate, at the conclusion of his term in 1796.[9] For the next 15 years he tended to affairs on his farm.[2] He was selected as a presidential elector in six consecutive elections, but these were his only appearances in public life during this period.[45]

Gabriel Slaughter was the favorite choice for governor of Kentucky in 1812. Only one impediment to his potential candidacy existed. Growing tensions between the United States, France, and Great Britain threatened to break into open war. With this prospect looming, Isaac Shelby's name began circulating as a possible candidate for governor. Slaughter, who lived near Shelby, visited him and asked whether he would run. Shelby assured him that he had no desire to do so unless a national emergency that required his leadership emerged. Satisfied with this answer, Slaughter began his campaign.[46]

The situation with the European powers grew worse, and on June 18, 1812 the United States declared war on Great Britain, beginning the War of 1812. Cries grew louder for Shelby to return as Kentucky's chief executive. On July 18, 1812, less than a month before the election, Shelby acquiesced and announced his candidacy.[47]

During the campaign Shelby's political enemies, notably Humphrey Marshall, criticized his response to Jefferson's second letter regarding the Genêt affair and questioned his loyalty to the United States.[48] Shelby contended that his noncommittal response to the letter was meant to draw the federal government's attention to the situation in the west.[48] He cited the agreement between Washington and the Spanish as evidence that his ploy had worked.[48] He also claimed to have known at the time he wrote the letter that the French scheme was destined to fail.[48]

Slaughter's supporters mocked Shelby's advanced age (he was almost 62), calling him "Old Daddy Shelby". One Kentucky paper even printed an anonymous charge that Shelby had run from the Battle of King's Mountain. Though few even among Shelby's enemies believed the story, his supporters and Shelby himself responded through missives in the state's newspapers. One supporter typified these responses, writing "It is reported that Colonel Shelby 'run [sic] at King's Mountain.' True he did. He first run [sic] up to the enemy... then after an action of about forty-seven minutes, he run [sic] again with 900 prisoners."[49]

As the canvass stretched into August, Shelby grew more confident of victory and began preparations to return to the state house. He predicted a victory of 10,000 votes; the final margin was more than 17,000.[50] When he took the oath of office, Shelby became the first Kentucky governor to serve non-consecutive terms. (James Garrard had been permitted to serve consecutive terms in 1796 and 1800 by special legislative exemption.)

Preparations for the war dominated Shelby's second term. Two days before his inauguration, he and outgoing governor Charles Scott met at the state house to appoint William Henry Harrison commander of the Kentucky militia. This was done in violation of a constitutional mandate that the post be held by a native Kentuckian. Already commander of the militias of Indiana and Illinois, Harrison picked up Kentucky volunteers at Newport before hurrying to the defense of Fort Wayne.[51]

Shelby pressured President James Madison to give Harrison command of all military forces in the Northwest.[44] Madison acceded, rescinding his earlier appointment of James Winchester.[51] On the state level, Shelby revised militia laws to make every male between the ages of 18 and 45 eligible for military service; ministers were excluded from the provision.[44] Seven thousand volunteers enlisted, and many more had to be turned away.[52] Shelby encouraged the state's women to sew and knit items for Kentucky's troops.[44]

Shelby's confidence in the federal government's war planning was shaken by the disastrous Battle of Frenchtown in which a number of Kentucky soldiers died.[44] He vowed to personally act to aid the war effort should the opportunity arise, and was authorized by the legislature to do so.[44] In March 1813, Harrison requested another 1,200 Kentuckians to join him at Fort Meigs.[53] Shelby dispatched the requested number, among whom was his oldest son James, under General Green Clay.[54][54] The reinforcements arrived to find Fort Meigs under siege by a combined force of British and Indians.[54] Clay's force was able to stop the siege, but a large number of them were captured and massacred by Indians.[55] Initial reports put James Shelby among the dead, but he was later discovered to have been captured and released in a prisoner exchange.[56]

On July 30, 1813, General Harrison again wrote Shelby requesting volunteers, and this time he asked that Shelby lead them personally.[44]Shelby raised a force of 3,500 volunteers, double the number Harrison requested.[1] Future governor John J. Crittenden served as Shelby's aide-de-camp.[57] Now a Major General, Shelby led the volunteers to join Harrison in a campaign that culminated in the American victory at the Battle of the Thames.[1]

In Harrison's report of the battle to Secretary of War John Armstrong, Jr., he said of Shelby, "I am at a loss to how to mention [the service] of Governor Shelby, being convinced that no eulogism of mine can reach his merit."[58] In 1817, Shelby received the thanks of Congress and was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal for his service in the war.[45] Friends of Shelby suggested he run for Vice President, but Shelby quickly and emphatically declined.[59]

Upon Shelby's leaving office in 1816, President Monroe offered him the post of Secretary of War, but he declined because of his age.[2]Already a founding member of the Kentucky Bible Society, Shelby consented to serve as vice-president of the New American Bible Society in 1816.[60] He was a faithful member of Danville Presbyterian church, but in 1816, built a small nondenominational church on his property.[61] In 1818, he accompanied Andrew Jackson in negotiating the Jackson Purchase with the Chickasaw.[4] He also served as the first president of the Kentucky Agricultural Society in 1818 and was chairman of the first board of trustees of Centre College in 1819.[2]

In 1820, Isaac Shelby was stricken with paralysis in his right arm and leg.[23] He died of a stroke on July 18, 1826, at his home in Lincoln County.[30] He was buried on the grounds of his estate, Traveller's Rest.[2] The state erected a monument over his grave in 1827.[27] In 1952 the Shelby family cemetery was given to the state government and became the Isaac Shelby Cemetery State Historic Site.[27]

Shelby's patriotism is believed to have inspired the Kentucky state motto: "United we stand, divided we fall". He was fond of The Liberty Song, a 1768 composition by John Dickinson, which contains the line "They join in hand, brave Americans all, By uniting we stand, by dividing we fall."[62] Though he is sometimes credited with designing the state seal, his public papers show that the design was suggested by James Wilkinson.[63]

Centre College began awarding the Isaac Shelby Medallion in 1972, and since then, it has become the college's most prestigious honor. Those awarded the Medallion exemplify the ideals of service to Centre and dedication to the public good that were embraced by Shelby during his time at Centre and in Kentucky.[64] Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isaac_Shelby

John Sevier (September 23, 1745 – September 24, 1815)

was an American soldier, frontiersman and politician, and one of the founding fathers of the State of Tennessee. He played a leading role, both militarily and politically, in Tennessee's pre-statehood period, and was elected the state's first governor in 1796. Sevier served as a colonel in the Battle of Kings Mountain in 1780, and commanded the frontier militia in dozens of battles against the Cherokeein the 1780s and 1790s.[1]

Sevier arrived on the Tennessee Valley frontier in the 1770s. In 1776, he was elected one of five magistrates of the Watauga Association and helped defend Fort Watauga against an assault by the Cherokee. At the outbreak of the War for American Independence, he was chosen as a member of the Committee of Safety for the association's successor, the Washington District. Following the Battle of Kings Mountain, he led an invasion that destroyed several Chickamauga towns in northern Georgia. In the 1780s, Sevier served as the only governor of the State of Franklin, an early, unsuccessful attempt at statehood by the trans-Appalachian settlers. He was brigadier general of the Southwest Territory militia during the early 1790s.

Sevier served six two-year terms as Tennessee's governor, from 1796 until 1801, and from 1803 to 1809, with term limits preventing a fourth consecutive term in both instances. His political career was marked by a growing rivalry with rising politician Andrew Jackson, which nearly culminated in a duel in 1803. After his last term as governor, Sevier was elected to three terms in the United States House of Representatives, serving from 1811 until his death in 1815.[1]

John Sevier was born in 1745 in Augusta County in the Colony of Virginia, near what is now the town of New Market (Sevier's birthplace is now part of modern-day Rockingham County).[2]:4 He was the oldest of seven children of Valentine "The Immigrant" Sevier and Joanna Goad. His father was descended from French Huguenots.[citation needed] He had immigrated to Baltimore in 1740 and gradually made his way to the Shenandoah Valley.[3]

Sevier's father worked variously, as a tavernkeeper, fur trader, and land speculator; and young John initially pursued a similar career path.[2]:5 At a young age, he opened his own tavern, and helped plant the town of New Market, near his birth site (the town claims Sevier as its founder).[4]

In 1761 at the age of 16, he married Sarah Hawkins, and settled into a life of farming. Some sources suggest Sevier served as a captain in the Virginia Colonial Militia, under George Washington, in Lord Dunmore's War in 1773 and 1774.[3]

In the early 1770s, Sevier and his brother began making trips to various settlements on the trans-Appalachian frontier, in what is now northeastern Tennessee.[2]:7 In late 1773, Sevier moved his family to the Carter Valley settlements along the Holston River. Three years later, he relocated further south to the Watauga settlements, in what is now Elizabethton, Tennessee.[2]:10The Wataugans had leased their lands from the Cherokee in 1772, and had formed a fledgling government known as the Watauga Association. Sevier was appointed clerk of the Association's five-man court in 1775, and was elected to the court in 1776.[5]

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 forbade English settlement on Indian lands, and as the Watauga settlements were in Cherokee territory, the British considered them illegal. In March 1775, the settlers purchased the lands from the Cherokee, with Sevier listed as a witness to the agreement.[6]:51 The British refused to recognize the purchase, however, and continued to demand the settlers leave. A group of Cherokees led by Dragging Canoe disagreed with the tribe's sale of the lands, and began making threats against the settlers.[6]:64

With the outbreak of the American Revolution, in April 1775, the Wataugans, most of whom were sympathetic to the Patriot cause, organized the Washington District, and formed a 13-member Committee of Safety. The committee, which included Sevier, submitted the "Watauga Petition" to Virginia in the Spring of 1776, formally asking to be annexed, but Virginia refused. (Historian J. G. M. Ramsey suggested Sevier wrote the petition, but later historians rejected this).[5] The Wataugans then petitioned North Carolina.

Fearing an invasion by Dragging Canoe, who was receiving arms from the British, the Overmountain settlers built Fort Caswell (commonly called Fort Watauga) to guard the Watauga settlements, and Eaton's Station to guard the Holston settlements. Sevier had begun building Fort Lee to guard settlements in the Nolichucky Valley, but after receiving word of an impending Cherokee invasion from Nancy Ward, the Nolichucky settlers fled to Fort Caswell, and Sevier soon followed.[6]:63–4

The Cherokee invasion began in mid-July 1776. Dragging Canoe went north to attack the Holston settlements, while a detachment led by Old Abraham of Chilhowee invaded the Watauga settlements. On July 21, Old Abraham's forces reached Fort Caswell, which was garrisoned by 75 militia commanded by John Carter, with Sevier and James Robertson as subordinates.[6]:64 Catherine Sherrill, Sevier's future wife, failed to make it into the fort before the gate was locked, but Sevier managed to reach over the palisades and pull her to safety.[6]:64 The fort's garrison beat back the Cherokee assault, and after a two-week siege, Old Abraham retreated. The Cherokee eventually sued for peace following an invasion of the Overhill country by William Christian in October 1776.[6]:65–6

The Wataugans sent five delegates, among them Sevier, to North Carolina's constitutional convention in November 1776. The new constitution created the "District of Washington," which included most of modern Tennessee. The new district elected Sevier to one of its two seats in the state's House of Representatives. The district became Washington County, North Carolina in 1777.[6]:67 Sevier was appointed lieutenant-colonel of the new county's militia.

Following the British victory, at the Battle of Camden, in August 1780, a detachment of Loyalists, under Major Patrick Ferguson, was dispatched to suppress Patriot activity, in the mountains. After routing a small force, under Charles McDowell, Ferguson sent a message to the Overmountain settlements, warning them that if they refused to lay down their arms, he would march over the mountains and "lay waste the country with fire and sword."[6]:86 Sevier and Sullivan County militia colonel Isaac Shelby agreed to raise armies and march across the mountains to engage Ferguson.[6]:86

On September 25, 1780, the Overmountain Men, as they came to be called, gathered at Sycamore Shoals to prepare for the march. This force consisted of 240 Washington County militia commanded by Sevier, 240 Sullivan County militia commanded by Shelby, and 400 Virginians commanded by William Campbell. To provide funds for the march, Sevier obtained a loan from John Adair, putting up his own property as collateral.[7]:144 The combined force departed across the mountains on September 26, eventually linking up with the remnants of McDowell's men.

On October 7, the Overmountain Men caught up with and surrounded Ferguson, who had entrenched his Loyalist forces atop Kings Mountain, near the present-day North Carolina-South Carolina border. Sevier's men comprised part of the south flank, along with the forces of Campbell and McDowell. Patriot forces initially failed to break through the Loyalist lines, but the frontier sharpshooters gradually decimated the American Loyalist ranks. At the height of the battle, Sevier and Campbell charged the high point of the Loyalist position, giving the Overmountain men a foothold atop the mountain.[7]:156 Ferguson was eventually killed trying to break through Sevier's line, and the Loyalists surrendered shortly afterward. Sevier's brother, Captain Robert Sevier, was mortally wounded in the battle.[7]:157

Upon returning from Kings Mountain, Sevier received word from Nancy Ward of an impending Cherokee invasion, and immediately organized a 300-man force and marched south.[7]:184 On December 16, 1780, he routed a Cherokee force at the Battle of Boyd's Creek, near modern Sevierville. A few days later, he was joined by a contingent of Virginia militia led by Arthur Campbell, and the combined forces continued south, occupying Chota on December 25. They captured and burned Chilhowee and Tallassee three days later. Sevier and Campbell proceeded as far as the Hiwassee River, where they burned the villages of Great Hiwassee and Chestoee, before beginning the march home on New Years Day.[7]:187–190

In February 1781, Sevier was commissioned colonel-commandant of the Washington County militia following the death of John Carter.[7]:193Shortly afterward, he embarked on an expedition against the Cherokee Middle Towns, which lay on the other side of the mountains in the vicinity of modern Bryson City, North Carolina. Emerging from the mountains in March, his 150-man force took the village of Tuckasegee by surprise, killing about 50 and capturing several others. Facing little opposition, he proceeded to destroy about 15 villages before returning home.[7]:193

In September 1782, Sevier set out on an expedition against Dragging Canoe and his band of Cherokee, who were now concentrated in a string of villages in northern Georgia and Alabama. Because Dragging Canoe's band had earlier been settled near the Chickamauga River, the European-American settlers called them by that name, but they were Cherokee. While the people were decentralized, this band was never identified separately from the Cherokee. Sevier defeated a small force near Lookout Mountain, and destroyed several Cherokee villages along the Coosa River.[7]:208

In June 1784, North Carolina, bowing to pressure, from the Continental Congress and eager to be rid of an expensive and unprofitable district, ceded its lands west of the Appalachian Mountains to the federal government. However, Congress did not immediately accept the lands, creating a vacuum of power in what is now Tennessee. In August 1784, Sevier served as president of a convention held at Jonesborough with the aim of establishing a new state.[6]:111 In March of the following year, he was elected governor of the proposed state,[8] which was named "Franklin" in honor of Benjamin Franklin.

In October 1784, North Carolina rescinded the cession and reasserted its claim to the Tennessee region. Sevier initially supported this, in part because he was offered a promotion to brigadier general, but was convinced by William Cocke to remain with the Franklinites.[6]:112 Though Sevier had popular support, a number of Washington Countians, led by John Tipton (1730–1813), remained loyal to North Carolina,[8] creating a situation in which two parallel governments– one loyal to Franklin and one to North Carolina– were operating in Tennessee. Both elected public officials. Relations between the two governments were initially cordial, though a rivalry developed between Sevier and Tipton.[9]

As North Carolina and Franklin competed for the loyalties of the residents of the area, Sevier became involved in intrigues with Georgia to gain control of Cherokee lands in what is now northern Alabama. He had taken out claims on several thousand acres of land. He even considered an alliance with Spain, whose Governor Esteban Rodríguez Miró tried to sway Sevier, but Sevier eventually abandoned the idea.

In June 1785, Sevier negotiated the Treaty of Dumplin Creek, in which the Cherokee gave up claims to lands south of the French Broad River as far as the Little River–Little Tennessee River divide. The following year, the Treaty of Coyatee extended the boundary to the Little Tennessee River, and the State of Franklin created three new counties (modern Cocke, Sevier, and Blount counties).[6]:117–120 The United States never ratified these treaties, however, and the fate of the settlers who moved into these areas remained in limbo for years.

In February 1788, the rivalry between Sevier and Tipton came to a head, in what became known as the "Battle of Franklin." While Sevier was away campaigning against the Cherokee, Tipton ordered some of his slaves seized for taxes supposedly owed to North Carolina. In response, Sevier led 150 militia to Tipton's farm, which was defended by about 45 loyalists. Both sides demanded the other surrender, and briefly exchanged gunfire. On February 29, two days after the siege began, loyalist reinforcements from Sullivan County arrived on the scene and scattered the Franklinites. Sevier retreated, though not before two men were killed. Many Franklinites were captured with two of Sevier's sons, but all subsequently released.[10]:133–6

In the Summer of 1788, a family of settlers was killed by renegade Cherokees, in Blount County, in what became known as the "Nine Mile Creek Massacre". In response, Sevier invaded and destroyed several Cherokee towns, in the Little Tennessee Valley. Several Cherokee leaders, met with Sevier, under a flag of truce to discuss peace, and a member of the murdered family, John Kirke, attacked the delegation and killed several chiefs, among them Old Tassel and Old Abraham of Chilhowee. This action enraged the Cherokee, and many of them threw their support behind Dragging Canoe.[6]:121

Following the Battle of Franklin, support for Sevier and the State of Franklin collapsed in areas north of the French Broad River, and North Carolina Governor Samuel Johnston issued a warrant for his arrest in July 1788.[10]:139 In October, after Sevier attacked Jonesborough store owner David Deaderick for refusing to sell him liquor, Tipton and his men apprehended the leader. He was sent to Morganton, North Carolina, to stand trial for treason, but was released by the Burke County sheriff, William Morrison (a Kings Mountain veteran), before the trial began.[10]:141

In January 1789, Sevier defeated a large Cherokee invasion led by John Watts at the Battle of Flint Creek near Jonesborough.[10]:159

In February 1789, Sevier took the Oath of Allegiance to North Carolina. He was elected to the North Carolina state senate, and was pardoned by North Carolina Governor Alexander Martin. When the senate convened in November 1789, Sevier worked in support of the state's ratification of the U.S. Constitution. After it was ratified on November 23, Sevier helped engineer a second cession act, which passed with little opposition in December, essentially handing over what is now the state of Tennessee to the federal government.[6]:124–7

To administer the new cession, Congress created the Southwest Territory in the Spring of 1790, which was administered under the Northwest Ordinance. Sevier was appointed brigadier general of the territorial militia, and fellow land speculator and North Carolina politician, William Blount, was appointed governor.[6]:127 In June 1791, Blount negotiated the Treaty of Holston, which resolved the land disputes with the Cherokee created by the Treaty of Dumplin Creek.

Just before the cession, the territory was the fifth congressional district of North Carolina, and Sevier was elected to represent it in the first Congress. By the time he arrived in New York City, the cession of Tennessee had taken place. Sevier was permitted to serve out his term despite the fact he was no longer representing an actual district.

In the Fall of 1793, following the Cherokee attack, on Cavett's Station west of Knoxville, Sevier led the territorial militia south into Georgia, where he defeated a Cherokee force at the Battle of Hightower and destroyed several villages.[6]:144 The following year, he was appointed by President Washington to the territorial council, a body which had a function similar to that of a state senate.[8] That same year, he was appointed to the first Board of Trustees of Blount College, the forerunner of the University of Tennessee.[11]

In 1796, the Southwest Territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Tennessee. Sevier missed the state's constitutional convention while serving on the territorial council in Washington, but was elected the new state's first governor. Sevier made the acquisition of Indian lands a priority, and consistently urged Congress and the Secretary of War to negotiate new treaties to that end.[6]:204

During his first term as governor, Sevier developed a rivalry with rising politician Andrew Jackson. In 1796, Jackson campaigned for the position of major-general of the state militia, but was thwarted when Sevier threw his support behind George Conway.[6]:211 Jackson also learned that Sevier had referred to him as a "poor pitiful petty fogging lawyer" in private correspondence.[6]:213 In 1797, Jackson, at the time a U.S. Senator, became aware of massive fraud that had taken place at North Carolina's Nashville land office in the 1780s, and notified the governor of North Carolina. When the governor demanded the office's documents, Sevier blocked their transfer, leading Jackson to conclude that Sevier was somehow involved in the scandal.[12]:34

After Sevier's third (two-year) term as governor, term limits prevented him from seeking a fourth consecutive term, and Archibald Roane was elected as his replacement. Both Sevier and Jackson campaigned for major-general of the militia, and when the vote ended in a tie, Roane chose Jackson.[6]:215When Sevier announced his candidacy for governor in 1803, Roane and Jackson made documents from the Nashville land office scandal public, and accused Sevier of bribery. Their efforts to smear Sevier were unsuccessful, however, and Sevier easily defeated Roane in the election.[6]:215

Following his inauguration, Sevier encountered Jackson in Knoxville. They had an argument during which Sevier accused Jackson of adultery in his marriage to Rachel Donelson. An enraged Jackson challenged Sevier to a duel, which Sevier accepted. The duel was to take place at Southwest Point, but Sevier's wagon stalled at Campbell's Station en route to the duel. As Jackson returned to Knoxville, he encounted Sevier's entourage. The two loudly exchanged insults, and Sevier's horse ran away, carrying his pistols. Jackson pointed his pistol at Sevier, who hid behind a tree. Sevier's son pointed his pistol at Jackson, and Jackson's second pointed his pistol at Sevier's son. Members of both parties managed to resolve the incident before bloodshed took place.[6]:215

In 1804, Sevier helped William C. C. Claiborne get appointed governor of the newly acquired Louisiana Territory, a position Jackson had sought.[12]:36 Jackson supported Roane in the state's gubernatorial election in 1805, but Sevier won with nearly two-thirds of the vote. Sevier's last campaign for governor was in 1807, when he defeated William Cocke.[12]:36–8

Term limits preventing him from a fourth consecutive term, Sevier sought one of the state's U.S. Senate seats in 1809, but the legislature chose Joseph Anderson. (Popular election of senators did not happen until after a constitutional amendment in the early 20th century.)[1] Sevier ran for the Knox County state senate seat, winning easily.[12]:38 In 1811, Sevier was elected to the U.S. Congress for the state's 2nd district. Sevier was a staunch supporter of the War of 1812, and President James Madison offered him a command in the army, but Sevier turned it down.[11]

According to the early Tennessee hisitorian Dr. J.G.M. Ramsey, Sevier attended the Lebanon In The Fork Presbyterian Church east of Knoxville with members of his family, but that Sevier was neither an elder or congregation member of the church. "His last wife was a member," wrote Ramsey, "but he was GuIlis-like and cared for none of these things." [13]

In 1815, Sevier died in the Alabama Territory while conducting a survey of lands which Jackson had recently acquired from the Creek tribe. He was buried along the Tallapoosa River near Fort Decatur.[1]

In 1889, at the request of Governor Robert Love Taylor, his remains were re-interred in the Knox County Courthouse lawn in Knoxville.[11] A monument was placed on the grave in 1893, in a ceremony that included a speech by historian Oliver Perry Temple. In 1922, the remains of his second wife, Catherine Sherill, were re-interred next to Sevier's. A monument recognizing his first wife, Sarah Hawkins, was placed at the site in 1946.[11]

In his book, The Lost State of Franklin, Kevin Barksdale points out that while Sevier was driven, at least in part, by a desire to acquire his own land claims in the trans-Appalachian region, he represents for many East Tennesseans, "rugged individualism, regional exceptionalism, and civic dignity."[10]:16 For nearly a century after his death, historians such as J. G. M. Ramsey and Oliver Perry Temple heaped unconditional praise upon Sevier, and romanticized various events in his life.[14][15] These events were clarified by later authors such as Theodore Roosevelt(Winning of the West) and Samuel Cole Williams (History of the Lost State of Franklin).[7]:18n

Several historians argue that the rivalry between John Sevier and Andrew Jackson was the root of the factionalism that divided East Tennessee and the rest of the state in subsequent decades.[12]:35[16] Pro-Sevier sentiment in East Tennessee gradually evolved into support for the Whig Party in the 1830s, and support for the Union during the Civil War. Following the war, East Tennessee remained one of the South's few predominantly Republican regions into the early 20th century, before the reversal of alignments from the 1960s on.

In the 1770s, Sevier established a plantation, Mount Pleasant, along the Nolichucky River south of Jonesborough. This residence inspired his nickname, "Nolichucky Jack."[3] He moved to Knoxville in 1797, where he began construction of what later became the James Park House. He completed only the foundation, however, before relocating to Marble Springs, a plantation he owned in South Knoxville.[11] A log cabin still standing at this site has been attributed to Sevier. But a dendrochronological analysis of the cabin's logs conducted by the University of Tennessee suggests the cabin was built well after his death.[17] Marble Springs has been designated a state historic site and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Numerous municipal and civic entities are named in honor of Sevier. These include Sevier County, Tennessee, and its county seat, Sevierville; Governor John Sevier Highway in south Knox County; John Sevier Middle School in Kingsport; and John Sevier Elementary School in Maryville. Other entities bearing his name include a coal-fired power plant operated by the Tennessee Valley Authority near Rogersville, a railroad classification yard operated by Norfolk Southern in east Knox County, and a dormitory at Austin Peay State University in Clarksville. Bonny Kate Elementary in South Knoxville and the Knoxville-based Bonny Kate Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution are named for Sevier's wife, Catherine Sherrill. The Johnson City-based John Sevier-Sarah Hawkins chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution is also named in honor of Sevier and his first wife.

In 1931, a statue of Sevier created by Leopold and Belle Kinney Scholz was dedicated at the National Statuary Hall Collection of the U. S. Capitol. Other monuments include a bust on the first floor of the Tennessee State Capitol, and Daughters of American Revolution monuments at Marble Springs in Knoxville and at Myrtle Hill Cemetery in Rome, Georgia. A monument to Sevier's father, Valentine Sevier ("the immigrant" as distinguished from John's brother, also named Valentine), has been placed at Sycamore Shoals State Historic Park in Elizabethton.

Tennessee’s first office building built specifically for state government offices is the John Sevier State Office Building. The six-story building opened in 1940 adjacent to the State Capital Building in downtown Nashville.

A marker also exists on the current grave of John Sevier on the lawn of the Old Knox County Courthouse. This marker claims his birth date was September 23, 1744 in contradiction to most sources that claim his birth year of 1745.

Although no evidence exists for the descent of Sevier from the royal family of St. Francis Xavier of Navarre, the name "Sevier" is an anglicized form of "Xavier"[3] and suggests the family originated in the village of Javier, Navarre. In the 17th century, some members of the Xavier family became Protestants (Huguenots). In 1685, following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, Sevier's grandfather, Don Juan Xavier, moved to London, and changed his name to John Sevier.[3] Sevier's father, Valentine "The Immigrant" Sevier (1712–1803), was born in London, and immigrated to the colonies in 1740.[3]

Sevier married Sarah Hawkins (1746–1780) in 1761. They had ten children: Joseph, James, John, Elizabeth, Sarah, Mary Ann, Valentine, Rebecca, Richard, and Nancy. Following her death, Sevier married Catherine Sherrill (1754–1836). They had eight children: Catherine, Ruthe, George Washington, Samuel, Polly, Eliza, Joanna, and Robert.[18]

Sevier's grandnephew, Ambrose Hundley Sevier (1801–1848), served as one of the first U.S. senators from Arkansas. Sevier County, Arkansas, is named for him. The Conway family, which dominated early Arkansas state politics, were cousins of the Seviers. Henry Conway, the grandfather of Ambrose Sevier and Arkansas's first governor, James Sevier Conway, was a friend of Sevier, and served as Treasurer of the State of Franklin. Two of Sevier's sons, James and John, married Conway's daughters, Nancy and Elizabeth, respectively.[19]

I've posted the entire articles from Wikipedia so I have the facts (as published there). If I want the sources of all the footnotes, I'll go over to Wikipedia...

No comments:

Post a Comment

Looking forward to hearing from you! If you leave your email then others with similar family trees can contact you. Just commenting falls into the blogger dark hole; I'll gladly publish what you say just don't expect responses.